Desire After Trauma: How Queer Bodies Rewrite Their Erotic Language

Desire does not disappear after trauma. It changes its grammar.

For queer people especially, erotic life is rarely a simple expression of bodily want. It is a language formed through constraint, secrecy, risk, and imaginative survival. Trauma—whether interpersonal, familial, medical, cultural, or political—can fracture that language. But fracture is not only loss. It is also the beginning of a rewrite.

In clinical work, queer desire often presents as translation: the psyche reworking its erotic codes in response to pain, history, and possibility. Long before trauma appears, queer bodies are already trained to read the world at an angle—to desire in metaphor, to relate through signals and subtexts, to decode cultural danger (Sedgwick 1990). Trauma does not erase this capacity; it alters its syntax. What was once a fluid erotic idiom may become muted, chaotic, or overdetermined. Yet psychoanalysis teaches that such reorganizations are intrinsic to the sexual: Freud’s concept of “polymorphous perversity” reveals a sexuality that is inherently adaptive and capable of inventive rearrangement (Freud 1905). Laplanche’s “enigmatic signifiers”—messages from the Other that exceed what the child can understand—frame sexuality itself as a lifelong project of translation (Laplanche 1999). In this view, trauma becomes an overwhelming message the psyche must metabolize: destructive, yes, but also an occasion for new meaning.

Contemporary queer and trans psychoanalytic thinkers widen the lens. Adrienne Harris’s idea of gender as “soft assembly” emphasizes that identity is not fixed but continuously reconfigured by relational, political, and sensory forces (Harris 2009). Trauma disrupts this assembly, but its interruption clarifies something fundamental: that queer and trans selves, like queer desire, are works in progress. Their mutability is not a sign of instability but of creative capacity. Understood this way, post-traumatic desire becomes a site of improvisation—an attempt to reorganize the self in the wake of psychic rupture.

Avgi Saketopoulou deepens this further. She argues that trauma does not simply shatter the psyche; it also generates the conditions for psychic expansion, the development of capacities that were previously unavailable (Saketopoulou 2023). Erotic life after trauma, in her view, can involve not the elimination of the traumatic imprint but its transformation into new erotic structures. This is not the sentimental claim that trauma is a gift. It is a recognition that the psyche works with what it has, insisting on aliveness even when desire feels dangerous or disorganized.

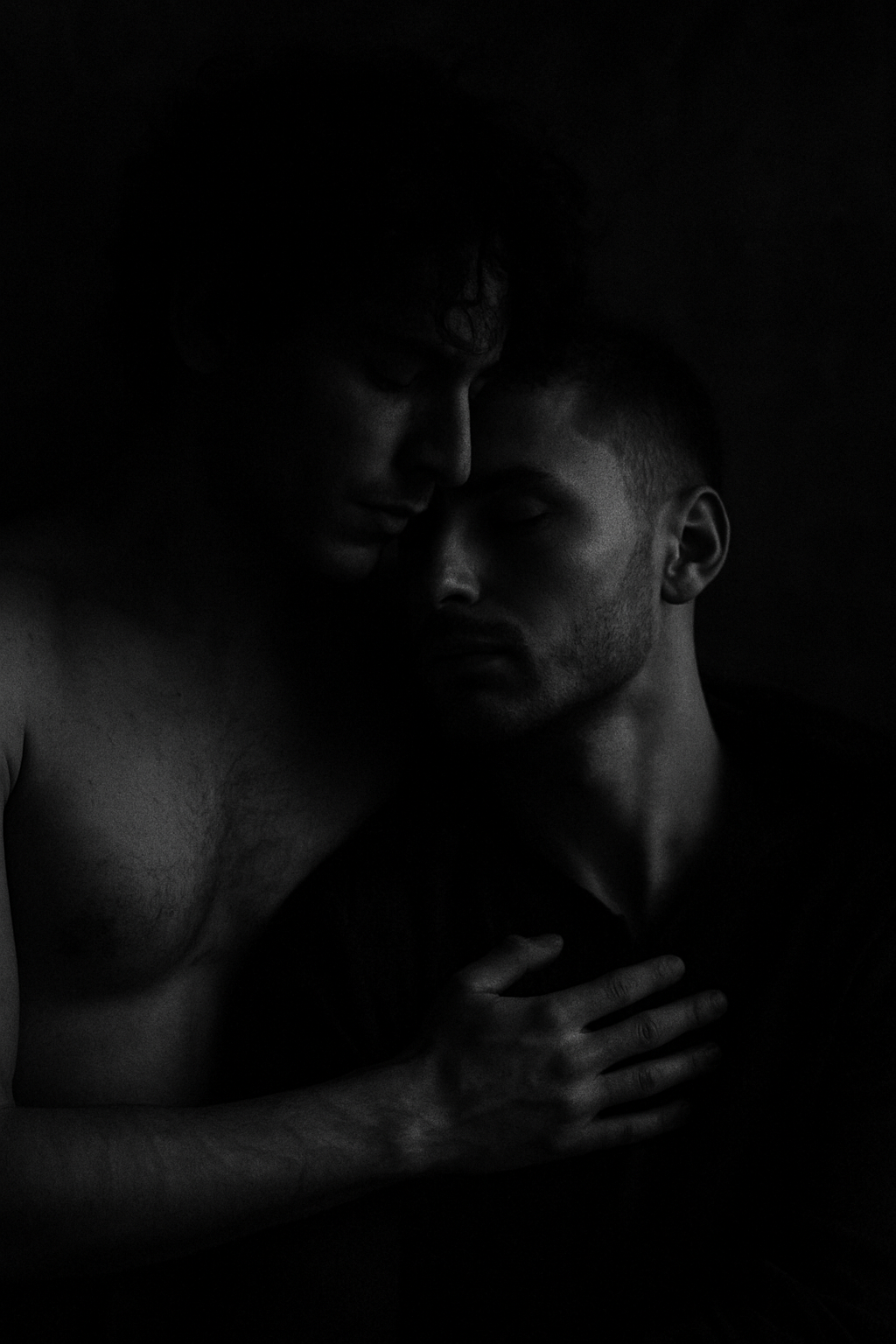

In practice, many queer survivors experience a suspension of desire: a worry that wanting has become contaminated, unsafe, or unreachable. Erotic muteness often precedes resurgence. Therapy becomes a space where desire can be spoken without sanitization or moral correction. The task is not to “correct” fantasy but to understand its textures—how it holds conflict, memory, fear, and hope. Winnicott’s notion of transitional space is essential here: a potential space where play, imagination, and symbol-making return (Winnicott 1971). Desire after trauma often emerges in this liminal zone, as a fleeting image or bodily curiosity that carries traces of both the old erotic language and its new, still-forming dialect.

Queer bodies rewrite their erotic language slowly. For some, the rewrite begins with mourning what was lost. For others, with the first moment of longing that feels unshadowed by fear. And for many, with paradox—the simultaneous desire for closeness and escape, intensity and retreat. The therapeutic encounter holds these contradictions with respect, trusting the psyche’s improvisational intelligence.

What emerges over time is not a restoration of the “pre-trauma” erotic self but a new erotic idiom: discontinuous, inventive, sometimes fragile, always real. The rewriting of desire is a form of authorship. It is a reclamation of erotic sovereignty from trauma’s grip. It is the queer body insisting it will not be defined solely by what wounded it. And often, it is the site of the deepest therapeutic work—the place where clients rediscover that their desire, altered and reassembled, still belongs wholly to them.

References

Freud, S. (1905). Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.

Harris, A. (2009). Gender as Soft Assembly.

Laplanche, J. (1999). Essays on Otherness.

Saketopoulou, A. (2023). Sexuality Beyond Consent: Risk, Race, Traumatophilia.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1990). Epistemology of the Closet.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and Reality.

Further Reading

Bersani, L. (1987). “Is the Rectum a Grave?”

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”.

Cvetkovich, A. (2003). An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures.

Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth (for the politics of bodily trauma).

Khan, M. M. R. (1974). The Privacy of the Self.

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity.

Snediker, M. (2008). Queer Optimism: Lyric Personhood and Other Felicitous Persuasions.

Stryker, S. (2008). Transgender History.

Wallin, J. (2007). “Foucault’s Body: The Return to Pleasure.”